bsacbob

Administrator (Retired)

- Joined

- Jul 1, 2012

- Location

- Chiang Rai

- Bikes

- Honda CRM-AR 250, Honda CRF 250-L, Suzuki V Strom XT 650 Honda XR250 Baja BMW F650GS

Article from the Asia Times.

UN Special Rapporteur on poverty and human rights plans to refer the reclusive authoritarian nation to the UN Human Rights Council for a host of abuses and failings.

communist-run Laos has had a relative knack for staying out of the news for its human rights abuses, endemic corruption and sub-par performance in providing services to its citizens. But now finally someone of prominence is speaking out.

Philip Alston, United Nations Special Rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights, visited the land-locked nation from March 18-28, winding up his trip with an unusually forthright 23-page statement on the bleak situation in Laos that will be submitted in June to the UN Human Rights Council.

Few observers think the UN report will have much impact on policy directives in Laos People’s Democratic Republic (PDR), which has been under the authoritarian rule of the communist Lao People’s Revolutionary Party since 1975.

Alston’s statement may, however, have impact on the way UN agencies and other multilateral aid organizations, key players in the country’s aid-dependent economy, comport themselves in one of the region’s most reclusive, poor and arguably abusive nations.

“Many interlocutors suggested to me that the UN in Lao PDR has largely failed to be a voice for the vulnerable, let alone for human rights, and that it has promoted an overtly optimistic picture of the country’s successes while sidestepping most of the many issues that it and the government deem to be ‘sensitive’,” Alston wrote in his report.

“What I hope to do with this statement is convince those that are more self-censoring to start speaking more freely,” he told Asia Times in an exclusive interview.

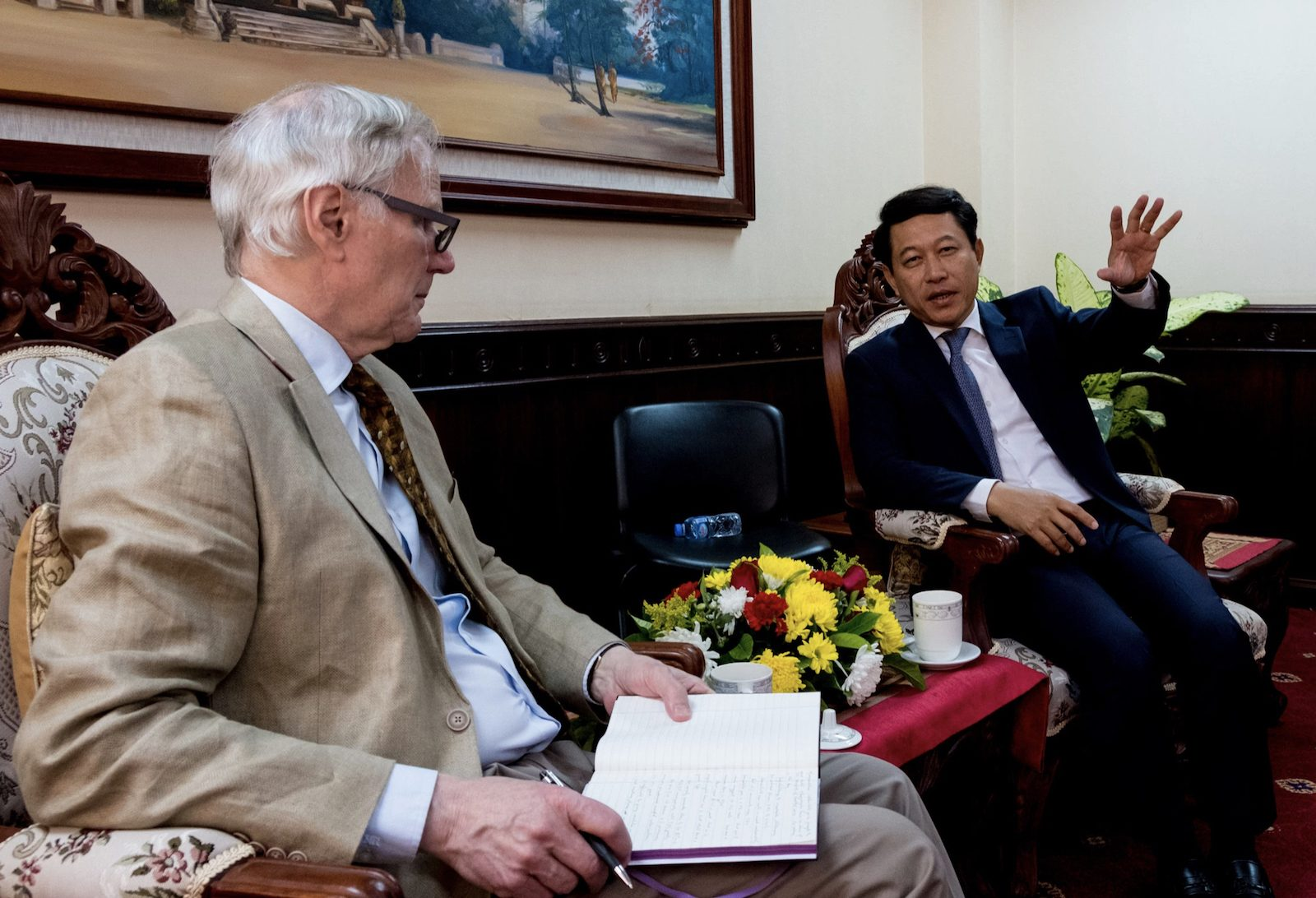

UN Special Special Rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights Philip Alston in a meeting with Lao Foreign Minister Saleumxay Kommasith in Vientiane, March 2019. Photo: UN/Bassam Khawaja.

he UN’s largely uncritical stance on the Lao government’s top-down management style is not news to the limited number of foreigners who have lived and worked in Laos since it began opening up to foreign aid and investment in the early 1990s.

Then the UN had near godlike sway over the government, which at the time was nearly wholly dependent on overseas development aid to keep what was then ranked as among the world’s poorest economies afloat.

But that narrative has since changed as China as recently started to pour aid and investment into the neighboring country, with no strings attached for improvements in rights, governance or transparency.

“They are too late,” said one foreign businessman about the UN’s apparent shifting stance on the country. “Twenty years ago they should have done it [forced reforms], but now they are competing against aid from China.”

Laos arguably has the most shackled press in Southeast Asia. It is the only country in mainland Southeast Asia where there are no mainstream media bureaus, in part due to the meager news pickings from the land-locked outpost but also because of an unofficial ban on foreign media in residence.

The lack of bad news emanating from Laos, including on issues of official corruption, is in part thanks to the regime’s gift for suppressing all forms of dissent and any form of criticism from civil society, even from the resident international community.

“There is a total climate of fear that permeates all civil society,” Alston told Asia Times. “And I would say there is a form of intimidation of the whole international community.”

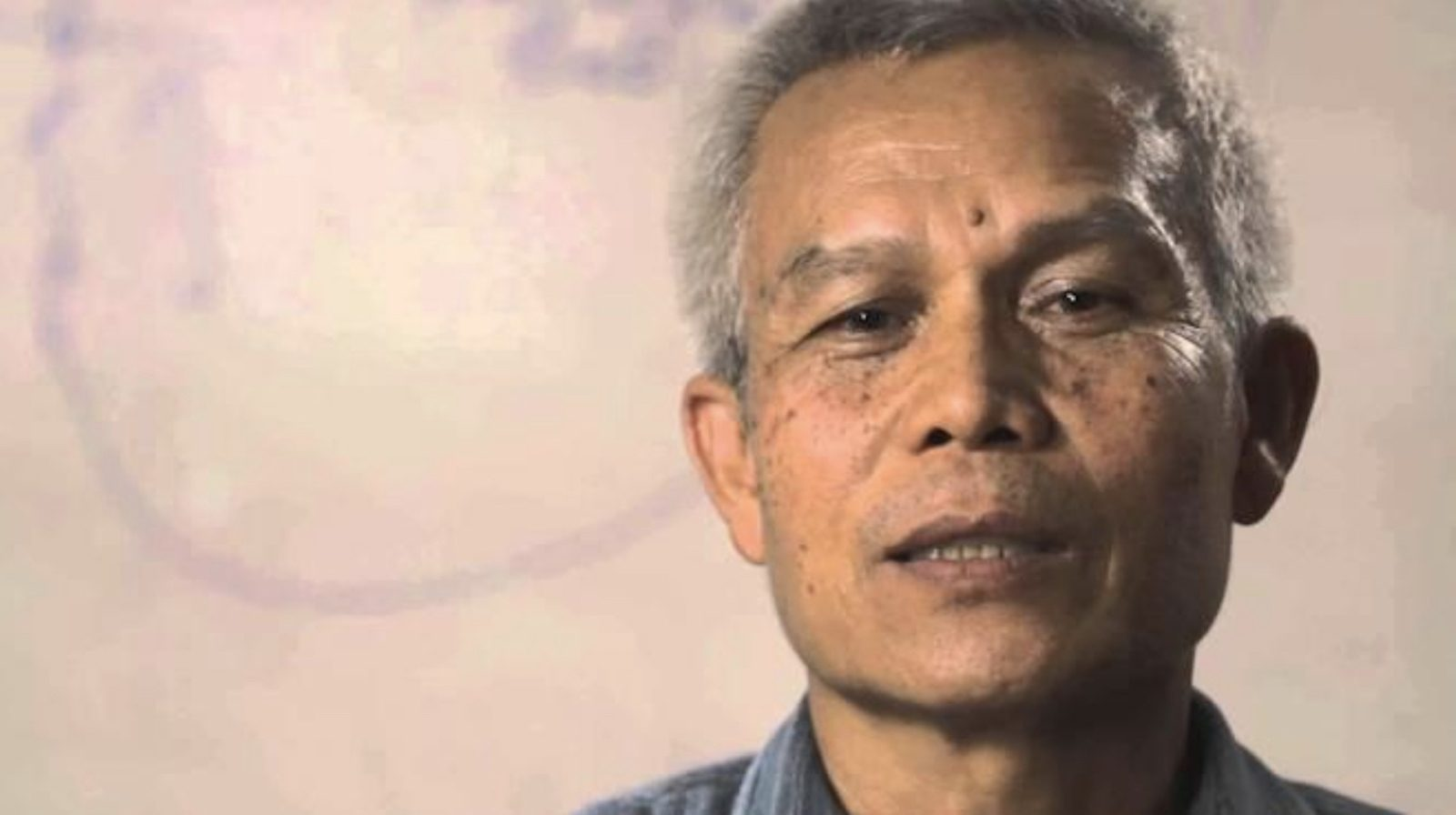

Prominent Lao activist Sombath Somphone has been missing after being disappeared by apparent plain-clothes officials in 2012. Photo: Twitter

Take, for instance, the well-known case of the mysterious disappearance of Sombath Somphone, a prominent civil society leader who was last seen at a police checkpoint in the capital of Vientiane in 2012.

Although CCTV footage showed Sombath being detained and driven away by what appeared to be plain-clothes policemen, the government has never acknowledged his arrest nor revealed his whereabouts, despite an unusually loud international outcry over the case.

The UN’s role in the Sombath case, critics say, was particularly pusillanimous. Prior to Sombath’s disappearance in 2012, the then UN resident coordinator had co-authored an opinion piece on participatory consultations with the civil society leader.

“After a draft of the article was circulated, the government of the Lao PDR, reportedly objected, causing the Resident Coordinator to take the highly unusual step of disavowing co-authorship and asking civil society groups to remove the article from their networks,” says Alston’s statement. “Just two months later, Somphone disappeared,” he notes.

Sombath’s unexplained disappearance sent a strong, if not chilling, message to the rest of civil society that even the mildest forms of dissent would not be tolerated.

Alston notes how UN agencies in Laos operate under severe constraints, which they willingly endure to maintain their operations in the poor nation.

For instance, they must seek permission from the government before visiting provincial areas, and must do so with government minders. UN reports, meanwhile, cannot be published without the prior permission of the government and are often shelved rather than publicly released.

“They don’t speak out because they know they will be thrown out,” Alston said in the interview. “But I think the international community doesn’t do itself any favors by not speaking honestly to the government.”

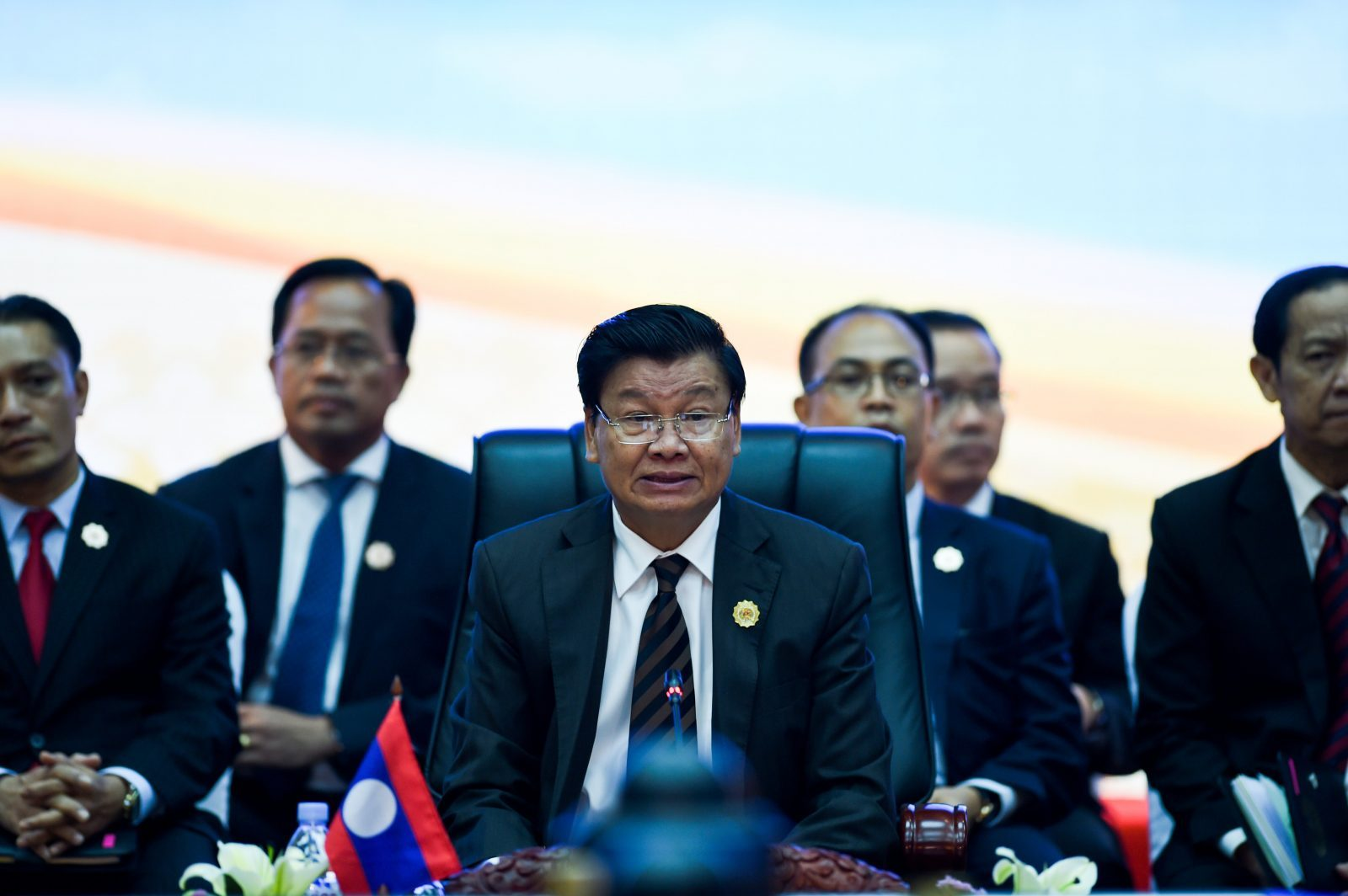

Lao Prime Minister Thongloun Sisoulith at an Asean Summit meeting in a file photo. Photo: AFP/Ye Aung Thu

According to Alston’s findings, there is a pressing need for frank talk, particularly on the country’s extreme poverty.

Laos has recently performed well on the macroeconomic front, chalking up an average of 6.5% gross domestic product (GDP) growth per annum since 2005. But that fast growth has not translated into a commensurate reduction in poverty.

“Far from providing an answer to poverty, Lao PDR’s economic growth strategies have too often destroyed livelihoods, created or exacerbated vulnerability, and lead to impoverishment for many groups,” Alston’s report claims.

The Lao PDR’s chief development strategies over the past three decades have included giving out 1,750 mining and plantation concessions to foreign investors covering about 40% of the countryside, according to Alston.

In particular, those concessions have enabled foreign investment in hydro-power dams that have displaced thousands of villagers and damaged riverine environments.

The projects can also end up threatening the lives and livelihoods of those around them, as was demonstrated by the breach of the Xe Pian Xe

Namnoy auxiliary dam in Attapeu province on July 23, 2018, a disaster that displaced thousands and killed scores, if not hundreds.

The government has since proven a poor provider of assistance to the victims, according to Alston.

Lao villagers take refuge on rooftops from floodwaters caused by the collapse of a hydropower dam in Attapeu province, July 23, 2018. Photo: AFP/Attapeu Today.

“Nine months later, approximately 3,750 people remain in limbo, living in crowded and hot temporary accommodation without information about

what the future holds, and with extremely limited financial report,” said Alston, who visited several affected sites in Attapeu on his trip.

Meanwhile, a joint-venture project with the Chinese government to build a US$6 billion medium-speed railway from China’s southern Yunnan province to Vientiane has also displaced hundreds of families, including through land concessions given to Chinese contractors along the line to help finance the deal.

To be sure, there has been some progress on the poverty front. According to the World Bank, the percentage of Lao people living on less than $1.90 a day, a measure of extreme poverty, fell from 52.4% in 1997 to 22.7% in 2012 (the last year for which data is available.)

The progress, however, has been highly unequal. Nearly 40% of the people living in rural areas are still in extreme poverty, compared with 10% in the cities. Minority groups, which make up 45% of the Lao population of 6.8 million have lagged behind the majority ethnic Lao-Tai at all economic levels.

“Ethnic minorities have more limited access to schools, with just 5% living in a village with an upper-secondary school, compared with 16% of Lao-Tai. Thirty-four percent of working-age ethnic minorities have no education, three times the rate of Lao-Tai, and just 15% have completed education compared to 60% of Lao-Tai,” Alston’s report says.

Laos’ performance in education has been particularly poor. According to Vientiane-based sources, the government’s spending on education in 2017 was just 3.1% of GDP, representing 13.4% of the budget. Health expenditure was even less at 1.7% of GDP, or 6.5% of the budget in 2017, comparatively low by regional standards, the report says.

A Lao Hmong hill tribe woman and her daughter walk down a street in the border town of Boten, a special economic zone land hired by China, in the northern province of Luang Namtha. Photo: AFP/Hoang Dinh Nam

Much of the budget is allocated towards road and other infrastructure building, areas prone to official skimming and corruption, while a growing portion will be needed for future foreign debt repayment, including to China.

While Alston’s critical statement will focus new attention on Laos’ sub-par performance in reducing poverty, it is less instructive about how to do so. There are broad suggestions on adopting pro-poor policies and increasing taxes on the private sector, but those are easier said than done in Laos’ context.

Unlike other Southeast Asian countries, Laos has a severely limited labor force and vast tracts of mountainous terrain that might be good for generating hydro-electricity but add substantial logistics costs for export oriented and other businesses.

The report, Vientiane-based economists and businessmen argue, also overlooks the strides made under current Lao Prime Minister Thongloun Sisoulith in tackling corruption and attempting to improve the business climate for FDI in areas other than environmentally-damaging mining and hydro-power.

“FDI is picking up and we have seen a higher quality of investment in the country,” said a Lao economist, citing a recent Japanese investment of $300 million in a hard disc drive factory in Vientiane.

A foreign investor who requested anonymity faults Alston’s statement for only focusing on the negative side of past FDI, without encouraging the government to pursue policies that promote a better climate for quality investment.

“There is no way the country is going to develop without FDI but the quality investors don’t get a chance here because we don’t have a level playing field,” said the investor. “That goes back to corruption. A lot of what Alston said goes back to corruption.”

UN Special Rapporteur on poverty and human rights plans to refer the reclusive authoritarian nation to the UN Human Rights Council for a host of abuses and failings.

communist-run Laos has had a relative knack for staying out of the news for its human rights abuses, endemic corruption and sub-par performance in providing services to its citizens. But now finally someone of prominence is speaking out.

Philip Alston, United Nations Special Rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights, visited the land-locked nation from March 18-28, winding up his trip with an unusually forthright 23-page statement on the bleak situation in Laos that will be submitted in June to the UN Human Rights Council.

Few observers think the UN report will have much impact on policy directives in Laos People’s Democratic Republic (PDR), which has been under the authoritarian rule of the communist Lao People’s Revolutionary Party since 1975.

Alston’s statement may, however, have impact on the way UN agencies and other multilateral aid organizations, key players in the country’s aid-dependent economy, comport themselves in one of the region’s most reclusive, poor and arguably abusive nations.

“Many interlocutors suggested to me that the UN in Lao PDR has largely failed to be a voice for the vulnerable, let alone for human rights, and that it has promoted an overtly optimistic picture of the country’s successes while sidestepping most of the many issues that it and the government deem to be ‘sensitive’,” Alston wrote in his report.

“What I hope to do with this statement is convince those that are more self-censoring to start speaking more freely,” he told Asia Times in an exclusive interview.

UN Special Special Rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights Philip Alston in a meeting with Lao Foreign Minister Saleumxay Kommasith in Vientiane, March 2019. Photo: UN/Bassam Khawaja.

he UN’s largely uncritical stance on the Lao government’s top-down management style is not news to the limited number of foreigners who have lived and worked in Laos since it began opening up to foreign aid and investment in the early 1990s.

Then the UN had near godlike sway over the government, which at the time was nearly wholly dependent on overseas development aid to keep what was then ranked as among the world’s poorest economies afloat.

But that narrative has since changed as China as recently started to pour aid and investment into the neighboring country, with no strings attached for improvements in rights, governance or transparency.

“They are too late,” said one foreign businessman about the UN’s apparent shifting stance on the country. “Twenty years ago they should have done it [forced reforms], but now they are competing against aid from China.”

Laos arguably has the most shackled press in Southeast Asia. It is the only country in mainland Southeast Asia where there are no mainstream media bureaus, in part due to the meager news pickings from the land-locked outpost but also because of an unofficial ban on foreign media in residence.

The lack of bad news emanating from Laos, including on issues of official corruption, is in part thanks to the regime’s gift for suppressing all forms of dissent and any form of criticism from civil society, even from the resident international community.

“There is a total climate of fear that permeates all civil society,” Alston told Asia Times. “And I would say there is a form of intimidation of the whole international community.”

Prominent Lao activist Sombath Somphone has been missing after being disappeared by apparent plain-clothes officials in 2012. Photo: Twitter

Take, for instance, the well-known case of the mysterious disappearance of Sombath Somphone, a prominent civil society leader who was last seen at a police checkpoint in the capital of Vientiane in 2012.

Although CCTV footage showed Sombath being detained and driven away by what appeared to be plain-clothes policemen, the government has never acknowledged his arrest nor revealed his whereabouts, despite an unusually loud international outcry over the case.

The UN’s role in the Sombath case, critics say, was particularly pusillanimous. Prior to Sombath’s disappearance in 2012, the then UN resident coordinator had co-authored an opinion piece on participatory consultations with the civil society leader.

“After a draft of the article was circulated, the government of the Lao PDR, reportedly objected, causing the Resident Coordinator to take the highly unusual step of disavowing co-authorship and asking civil society groups to remove the article from their networks,” says Alston’s statement. “Just two months later, Somphone disappeared,” he notes.

Sombath’s unexplained disappearance sent a strong, if not chilling, message to the rest of civil society that even the mildest forms of dissent would not be tolerated.

Alston notes how UN agencies in Laos operate under severe constraints, which they willingly endure to maintain their operations in the poor nation.

For instance, they must seek permission from the government before visiting provincial areas, and must do so with government minders. UN reports, meanwhile, cannot be published without the prior permission of the government and are often shelved rather than publicly released.

“They don’t speak out because they know they will be thrown out,” Alston said in the interview. “But I think the international community doesn’t do itself any favors by not speaking honestly to the government.”

Lao Prime Minister Thongloun Sisoulith at an Asean Summit meeting in a file photo. Photo: AFP/Ye Aung Thu

According to Alston’s findings, there is a pressing need for frank talk, particularly on the country’s extreme poverty.

Laos has recently performed well on the macroeconomic front, chalking up an average of 6.5% gross domestic product (GDP) growth per annum since 2005. But that fast growth has not translated into a commensurate reduction in poverty.

“Far from providing an answer to poverty, Lao PDR’s economic growth strategies have too often destroyed livelihoods, created or exacerbated vulnerability, and lead to impoverishment for many groups,” Alston’s report claims.

The Lao PDR’s chief development strategies over the past three decades have included giving out 1,750 mining and plantation concessions to foreign investors covering about 40% of the countryside, according to Alston.

In particular, those concessions have enabled foreign investment in hydro-power dams that have displaced thousands of villagers and damaged riverine environments.

The projects can also end up threatening the lives and livelihoods of those around them, as was demonstrated by the breach of the Xe Pian Xe

Namnoy auxiliary dam in Attapeu province on July 23, 2018, a disaster that displaced thousands and killed scores, if not hundreds.

The government has since proven a poor provider of assistance to the victims, according to Alston.

Lao villagers take refuge on rooftops from floodwaters caused by the collapse of a hydropower dam in Attapeu province, July 23, 2018. Photo: AFP/Attapeu Today.

“Nine months later, approximately 3,750 people remain in limbo, living in crowded and hot temporary accommodation without information about

what the future holds, and with extremely limited financial report,” said Alston, who visited several affected sites in Attapeu on his trip.

Meanwhile, a joint-venture project with the Chinese government to build a US$6 billion medium-speed railway from China’s southern Yunnan province to Vientiane has also displaced hundreds of families, including through land concessions given to Chinese contractors along the line to help finance the deal.

To be sure, there has been some progress on the poverty front. According to the World Bank, the percentage of Lao people living on less than $1.90 a day, a measure of extreme poverty, fell from 52.4% in 1997 to 22.7% in 2012 (the last year for which data is available.)

The progress, however, has been highly unequal. Nearly 40% of the people living in rural areas are still in extreme poverty, compared with 10% in the cities. Minority groups, which make up 45% of the Lao population of 6.8 million have lagged behind the majority ethnic Lao-Tai at all economic levels.

“Ethnic minorities have more limited access to schools, with just 5% living in a village with an upper-secondary school, compared with 16% of Lao-Tai. Thirty-four percent of working-age ethnic minorities have no education, three times the rate of Lao-Tai, and just 15% have completed education compared to 60% of Lao-Tai,” Alston’s report says.

Laos’ performance in education has been particularly poor. According to Vientiane-based sources, the government’s spending on education in 2017 was just 3.1% of GDP, representing 13.4% of the budget. Health expenditure was even less at 1.7% of GDP, or 6.5% of the budget in 2017, comparatively low by regional standards, the report says.

A Lao Hmong hill tribe woman and her daughter walk down a street in the border town of Boten, a special economic zone land hired by China, in the northern province of Luang Namtha. Photo: AFP/Hoang Dinh Nam

Much of the budget is allocated towards road and other infrastructure building, areas prone to official skimming and corruption, while a growing portion will be needed for future foreign debt repayment, including to China.

While Alston’s critical statement will focus new attention on Laos’ sub-par performance in reducing poverty, it is less instructive about how to do so. There are broad suggestions on adopting pro-poor policies and increasing taxes on the private sector, but those are easier said than done in Laos’ context.

Unlike other Southeast Asian countries, Laos has a severely limited labor force and vast tracts of mountainous terrain that might be good for generating hydro-electricity but add substantial logistics costs for export oriented and other businesses.

The report, Vientiane-based economists and businessmen argue, also overlooks the strides made under current Lao Prime Minister Thongloun Sisoulith in tackling corruption and attempting to improve the business climate for FDI in areas other than environmentally-damaging mining and hydro-power.

“FDI is picking up and we have seen a higher quality of investment in the country,” said a Lao economist, citing a recent Japanese investment of $300 million in a hard disc drive factory in Vientiane.

A foreign investor who requested anonymity faults Alston’s statement for only focusing on the negative side of past FDI, without encouraging the government to pursue policies that promote a better climate for quality investment.

“There is no way the country is going to develop without FDI but the quality investors don’t get a chance here because we don’t have a level playing field,” said the investor. “That goes back to corruption. A lot of what Alston said goes back to corruption.”